My sermon on Sunday explored the connection between ignorance of God and unbelief. When God's people don't know his history, his promises, and the worldview he instantiates in the Bible, they cannot have confidence in him. In their worship, God becomes a mystery guest.

The broad ignorance of American evangelicals about the faith they claim is well-documented. But I have many questions. Specifically, what kind of ignorance are we facing? In order to have abiding faith in God, what should evangelicals learn? And how?

Many have decried evangelicals' biblical illiteracy, which I have seen all too often. Once, at a banquet where I'd been invited to speak, I was seated next to a woman who'd been highly involved at the host church. She told me about a T.V. movie she had seen: a young man in olden times was sold into slavery by his own brothers, was taken to a foreign country, even wound up in prison, but eventually became the nation's ruler. The movie was really exciting, she said, adding brightly, "And it was based on a true story!"

There is, beyond this, a lack of doctrinal knowledge. People no longer learn a system of teaching about the faith, a biblically derived intellectual framework. Some even attack doctrine as a hindrance to faith.

Further, people lack a knowledge of devotional disciplines, which the spiritual formation movement now aims to teach. Further yet, there is a broad decline in practical family skills like parenting, budgeting, and communication -- skills that used to be inherited but now have to be taught.

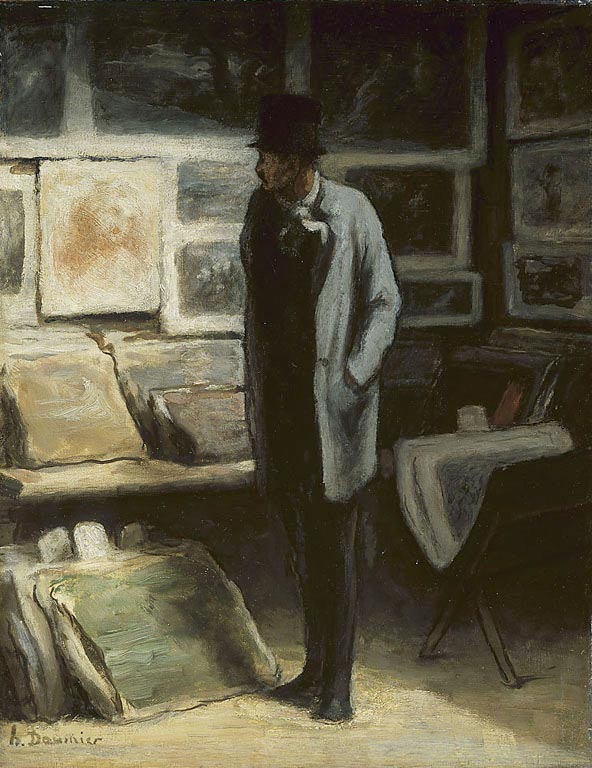

All these species of ignorance populate evangelical pews. Churches are filled with men and women who are confident socially -- who smile and laugh with their friends, and who are eager to be involved in activities. Many of the people have confident political views as well. But let God become the sole focus of conversation, and their eyes show a certain retreat, a vulnerability and wariness.

So, what are we dealing with?

First, we are oppressed not such much by individual ignorance as by cultural ignorance. Regardless of what individuals may or may not know, communities don't know enough. People do not have a large enough fund of shared knowledge.

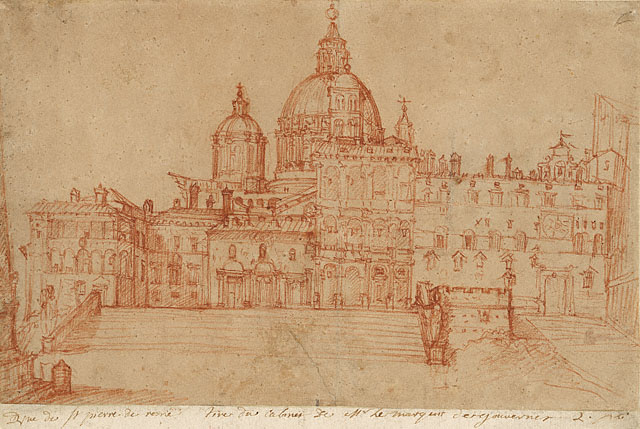

Cultural knowledge is, as the rhyming preachers say, caught not taught. It is gained in the rhythms of a way of life. A person learns the story of Joseph deeply -- learns Joseph's traumas, learns his importance, learns the Lord's providence in his life -- not because she hears about him in a class, but because in her church Joseph is still alive. He is a constant reference point, an icon of God's faithfulness in human suffering. Joseph is shared.

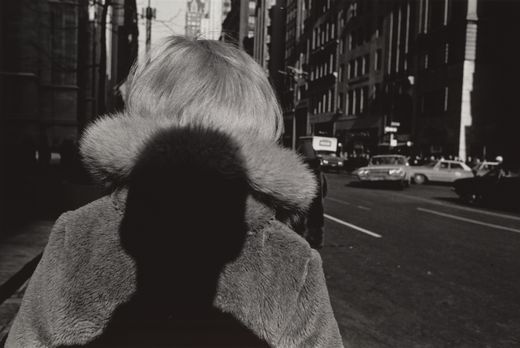

Cultural knowledge is not fully conscious. The bulk of it is prejudicial. It is not theoretical or abstract, but instantiated. It is not even coherent, in the sense that the community has fully untangled all its paradoxes. Cultural knowledge is gut-level.

Which leads to a second point: evangelical ignorance is not merely a dearth of facts but of emotion. Evangelicals do not recognize the significance of the Bible, of doctrine, of devotional and practical godliness -- recognize the significance at gut-level. Spiritual realities leave them unmoved.

When people do not have shared knowledge, they do not feel deeply enough.

A Christian way of life in America has been lost. Its rhythms of community are loose, and its shared symbols are neglected or sentimentalized. For a long time now, evangelicalism has been a parasite on consumerism, having little vitality or nourishment on its own. This is why evangelicals become wary when they're confronted with God himself. They do not share him; they share worldliness.

Pastors have been frantically trying to replace cultural knowledge with mere training. Give the people more facts, more tools, more tips.

In particular, pastors have been trying to make applications of biblical knowledge using generalizations. Joseph's story isn't "practical enough" as Genesis narrates it. In order to become "practical," the man Joseph has to be atomized into a series of "principles" that can be "applied" to "real situations in your life." So, keep a good attitude in hardship. Always do your best, whether you're in prison or in power. Just like Joseph in olden times. See ya next week.

This training approach is not necessarily wrong. But it won't educate the kind of ignorance we face: it won't build up a community's shared knowledge. It won't train people's guts.

If evangelicals are going to believe God deeply again, the preacher will need to address his own ignorance. He will need to explore how the Bible instantiates truth artistically -- through poems, narratives, and, yes, sermons. He will need to find how he can instantiate the same truth, bringing the Bible's instances to life with such specificity and detail that no one can ignore the implications. He will need to recover a sense of drama with God as the central character, not human beings.

In other words, evangelical ignorance results from the emotional detachment of evangelical preachers.